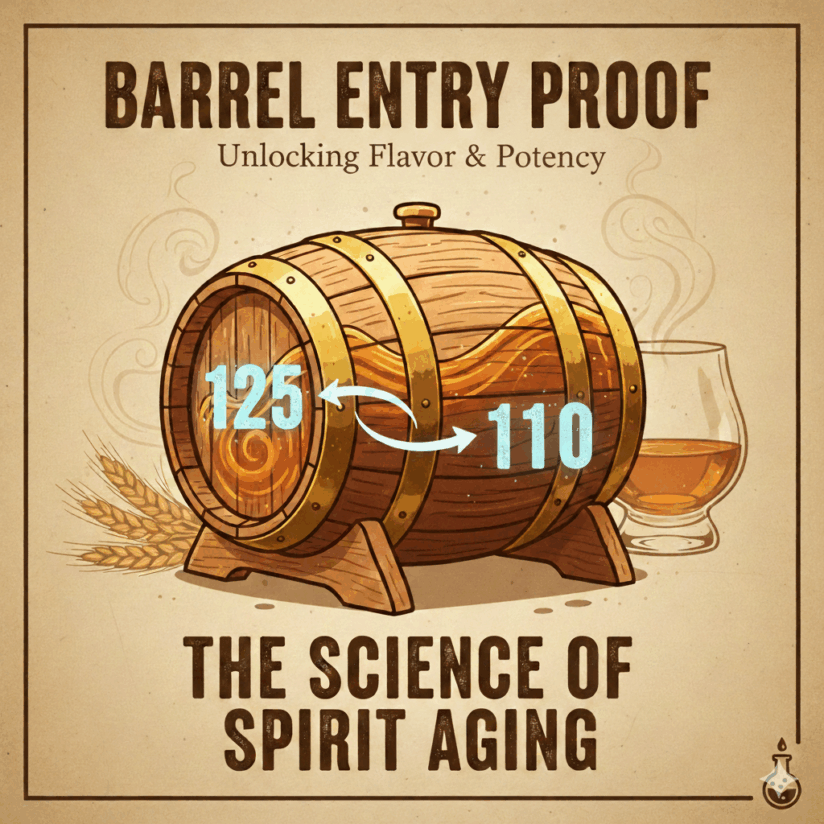

Entry Proof & The Science of Spirit Aging

What happens behind the scenes before your favorite bourbon hits the shelf? While we focus on alcohol proof (the number on the label), there’s a lesser known number that arguably matters even more: entry proof. This is the alcohol content of the spirit the moment it’s poured into a fresh charred oak barrel.

It’s not just a technicality—it’s where the soul of the whiskey is born.

The Golden Number

In the modern whiskey world, the legal maximum entry proof for bourbon is 125 proof (or 62.5% ABV). If you’re touring a major distillery today, you’ll find that 125 is the standard “industry norm.” Why? Because it’s efficient. High proof means you are putting more “potential whiskey” into a single barrel. If you barrel at a lower proof, you’re filling those barrels with more water, which means you need more barrels, more warehouse space, and more money to produce the same amount of booze.

The Legal History

Entry proof hasn’t always been this high. For over a century, the standard was much lower.

• Pre-1962: The legal limit was 110 proof. Most “old school” distillers hovered around 100 to 107 proof.

• The Big Change: In 1962, the U.S. government raised the limit to 125 proof.

This was a massive win for big-budget distilleries looking to cut costs, but it fundamentally changed the flavor profile of American whiskey.

High vs. Low

Is one better than the other? Not necessarily—it depends on what flavor the master distiller is chasing.

The Case for Low Entry Proof (100–110 Proof)

Some of the most respected names—like Maker’s Mark (110) and Michter’s (103)—stubbornly stick to lower entry proofs. Here’s why:

• Better Sugar Extraction: Water is a better solvent for wood sugars (hemicellulose) than alcohol is. Lower proof means more water in the barrel to dissolve those yummy vanillas and caramels.

• Fewer Harsh Tannins: Alcohol is a “hot” solvent that aggressively pulls out bitter tannins and lignins. Lower proof can lead to a smoother, less “woody” or astringent finish.

• Less Dilution: Since you start closer to your bottling strength, you don’t have to add as much water at the end. This keeps the concentrated “barrel character” intact.

The Case for High Entry Proof (110–125 Proof)

The big players like Buffalo Trace and Heaven Hill often utilize the higher end of the spectrum.

• Efficiency: As mentioned, you get more whiskey per barrel. It’s the “economies of scale” approach.

• Boldness and Spice: Higher proof extracts more of those “spicy” wood compounds. If you want a whiskey that has a heavy oak punch and a lot of structure, high entry proof is your friend.

• Longevity: High-proof spirits often stand up better to very long aging (10+ years), as the higher alcohol content acts as a preservative against some of the more volatile changes that happen in a warehouse.

Overall, your choices vary. I’m a fan of brands with both low and high entry proofs. But you must research this to discover what you like, where your palate sits. Also, some distilleries are less transparent than others about this, and you won’t find it on the label. But a simple Google search will lead you to a variety of articles on this subject if you specify the distillery in your search and wish to take a deeper dive into it.

Leave a Reply

Become an insider and receive weekly advice, tips, and insight on all things whiskey

.

Weekly tips, reviews and recommendations to help you enjoy whiskey life to the fullest.

JOIN THE LIST

Sippin' With Jordan Davis

sippin' with the stars

Million Dollar Cowboy Bar WY

old fashioned aF

5 Steps To Sip and Savor Whiskey

whiskey 101

COMMENTS